2016 numbers: CNS orphan drugs growing

With 2016 numbers now available, the number of orphan drugs in development for neurological indications is looking quite positive. I have reviewed the numbers of orphan drug designations and approvals by FDA in 2016 to see how popular are neurological orphan drugs today and what the trend is for the near future.

The FDA approved only 22 new drugs last year, a big fall from the 45 approvals it granted in 2015. But not all approvals are for new molecules, there are also many approvals that are new indications of previously approved drugs, also known as “drug repurposing”, so the total number of approvals is actually higher than what news outlets otherwise suggest (see here and here).

We see many cases of drug repurposing in rare diseases, so I have looked at the total number of orphan drug approvals and the total number of orphan drug designations in 2016, including new molecules as well as new indications (or designations) for already approved drugs.

THE NUMBERS

In 2016 the FDA approved 37 orphan drugs, out of which only two were for neurological indications: Spinraza (nusinersen) from Biogen for spinal muscular atrophy, and Carnexiv (carbamazepine injection) from Lundbeck for epilepsy as an alternative to oral carbamazepine. The rest of the approvals, as usual, were dominated by oncology.

This means that only 5% of all orphan drug approvals during 2016 were for neurological indications.

However when we look at the drugs that received an orphan drug designation last year the picture is much better for neurology.

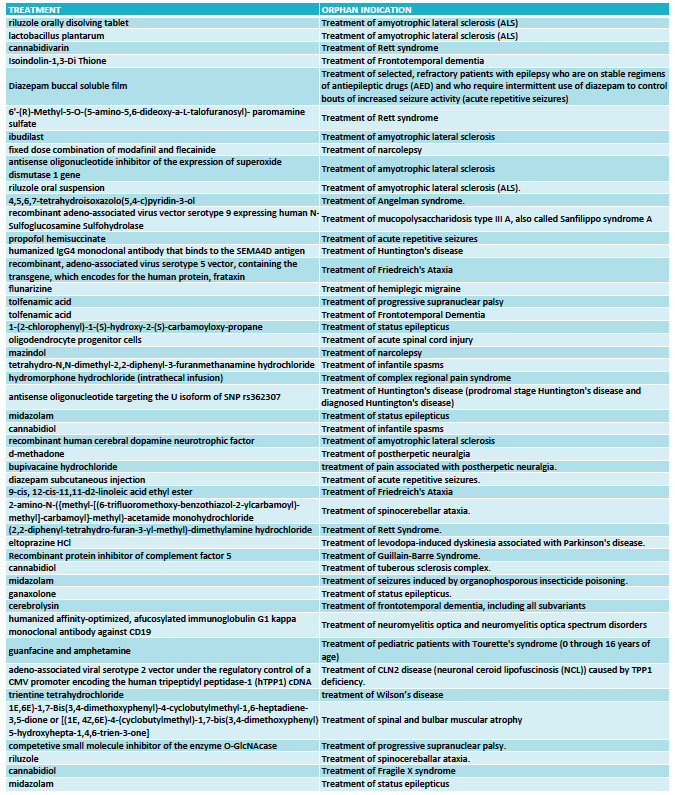

The FDA granted 333 orphan drug designations last year. This number includes some diagnostic reagents so I have only included in my analysis 325 orphan drug designations for the treatment of rare indications. Out of these, 48 orphan drug designations were for neurological indications (see full list at the end of the article) and again oncology dominated in the remaining cases.

With 48 designations in 2016, neurology accounted for 15% of the cases, indicating that the percentage of orphan drugs approvals for neurological indications could triple in the near future.

THE BREAKDOWN

Among the 48 designations, the largest area was neurodegeneration, followed by epilepsy. This reflects two important trends in CNS drug development.

One trend is to target orphan indications when the large indications become too crowded. This is the case of epilepsy, where many of the orphan designations are for drugs that could have efficacy in broader epilepsies -and in many cases are already approved for broader forms of epilepsy- but choose to seek approval for a specific syndrome or type of seizures (such as acute repetitive seizures) to reduce competition.

The other trend is to use rare diseases to obtain the initial clinical proof-of-concept for a compound that is eventually aimed at targeting the large indications. This has became very common in the neurodegeneration field where a Phase 3 failure can cost many hundreds of millions, so de-risking the program in a smaller and more uniform patient population is an excellent development strategy. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) was traditionally the rare disease model for neurodegenerative compounds and had 6 orphan drug designations in 2016, and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) have emerged more recently as attractive rare diseases to re-risk molecules in development for Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease.

What I classified as neurodevelopmental diseases includes the syndromes of Rett, Angelman, Fragile X and tuberous sclerosis complex. I could have classified some of these as epilepsy based on the trial endpoint, like is the case of the orphan drug designation for treating tuberous sclerosis complex with cannabidiol. Likewise, I could classify some of the epilepsy syndromes as neurodevelopmental diseases given the clinical presentation but kept them under epilepsies for this analysis purposes because of the seizure-focused trial endpoints. Collectively, all of these neurological syndromes characterized by seizures, cognitive, behavioral and motor problems are very popular within the orphan drug space.

Among the remaining designations I found interesting 4 treatments for ataxias (Friedreich's ataxia and spinocerebellar ataxia), and two for narcolepsy.

THE FUTURE

Looking at the 2016 orphan drug designations in neurology (see the full list at the end of the article) I can see how rare diseases are facilitating a revival of a field that has suffered from some areas being overcrowded and others being extremely difficult to pursue (think of Alzheimer’s disease). By providing smaller and more homogenous populations rare diseases offer the possibility of shorter and cheaper development programs, opening the field to smaller companies that could now have developed a clinical asset without partnering with a large company. And the genetic nature of many of the rare diseases has also offered us targets that increase the likelihood of succeeding in those trials versus symptomatic approaches in heterogeneous populations.

But not all is opportunistic strategies to reduce competition or de-risk programs. We are also seeing a growing number of gene therapy or antisense approaches in development that target the cause of these rare diseases, including 2016 designations for Sanfilippo syndrome, Friedreich's ataxia and Batten disease and antisense oligonucleotides for ALS and Huntington's disease.

Based on these numbers the future looks promising for neurological orphan drugs, with numbers that could triple and the development of disease-modifying treatments.

Ana Mingorance PhD

FULL LIST ORPHAN DRUG DESIGNATIONS FOR NEUROLOGY - FDA 2016