Impatient series #2 – What are companies looking for when choosing a rare disease

As part of these Series I will write about what patient organizations can do towards advancing research, even before a company gets interested in their disease. But before I can address that, we need to first define what gets companies interested in a disease in particular. That will then serve as the goal for patient groups: get your disease field to the point where it can attract companies.

As a side note, some diseases will be so rare that they won’t be able to attract companies. In those cases, if patient organizations need to carry out all of the research and development activities, they will still need a field that is mature enough to support drug development efforts.

I will address this in two parts: first, why companies get interested in rare diseases, and second, why do they choose one rare disease vs another.

PART 1 – CHOOSING ORPHAN

The number of orphan products in development keeps growing every year. Therapies are called orphan when they target a rare disease, which were traditionally orphan in the sense of not having any medicine to treat them. But nowadays some rare diseases have multiple “orphan” drugs to treat them, such as cystic fibrosis, and they are still called orphan drugs.

Companies have been driven towards rare diseases for a combination of reasons. The main ones are probably a market push (away from large markets) and a technology pull (towards rare diseases):

A market push: some of the larger markets got so crowded that it became very difficult for companies to get a competitive price. This has been called the “better than the Beatles” problem. Imagine if every new musician would need to show that they are better than the Beatles in order to get a record out – this is what new drugs must demonstrate in order to get approved and be successful in the market. The rare disease space, however, represents a broad landscape of virgin diseases, for which no drug (or Beatles' song) has ever been approved, and where an effective and safe drug will be commercially rewarded.

A technology pull: with the development of new technologies, particularly genomics, we have been able to understand that what we thought were common diseases are in fact a collection of separate (genetic) rare diseases. Other technologies such as gene therapy and antisense therapy have also enabled us to treat these diseases, in a way that we could have never imagined some years ago.

Drugs developed to treat rare diseases also enjoy of some regulatory and market incentives, which were developed by the regulatory agencies to attract drug developers to this space. The most valuable one is probably the 7 to 10 years (US vs EU) of market exclusivity after approval during which no competitor can have a similar drug approved for the same disease (a generic). But this aspect is less important for patient organizations. Instead we should try to understand how the market and the technology might drive a company to our rare disease.

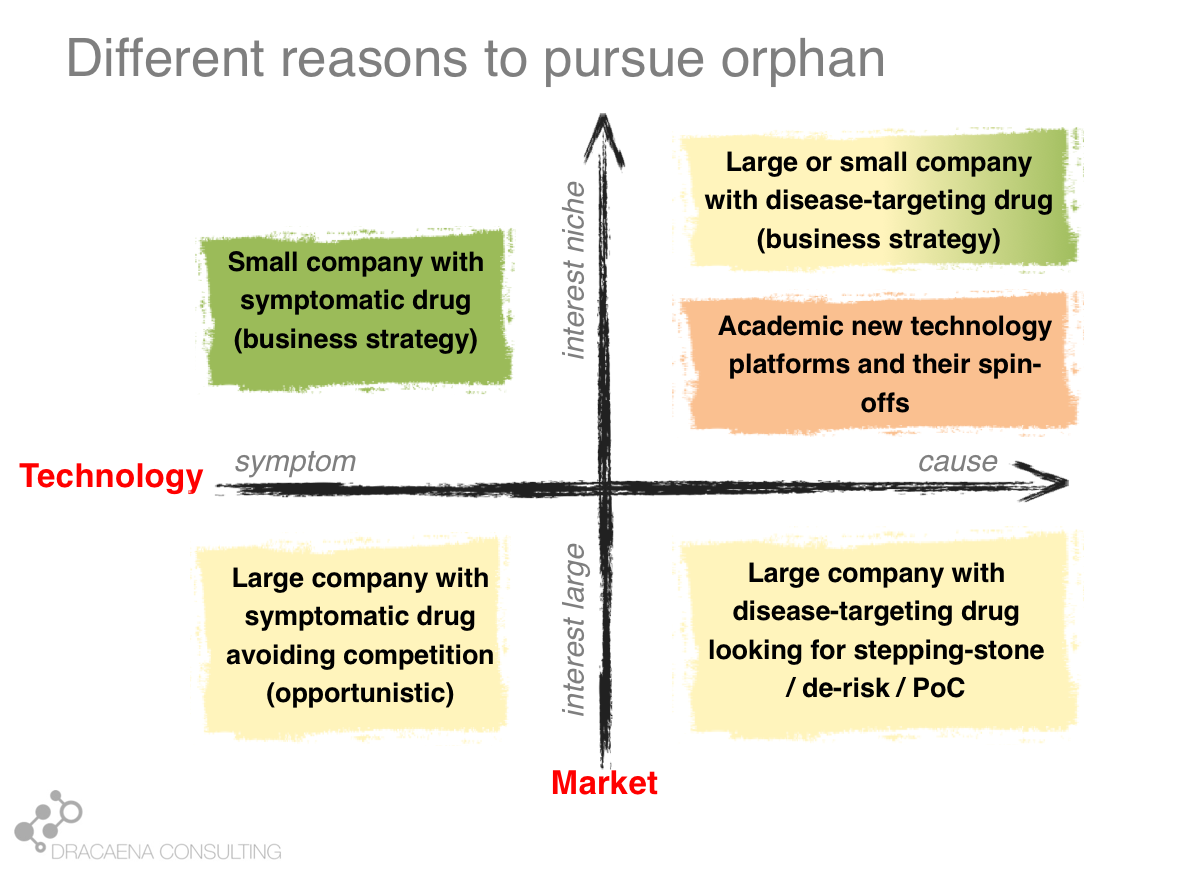

Looking at the interaction between the market push and the technology pull we can differentiate 4 types of companies that get interested in rare diseases or 4 types of programs within a company that might be directed towards a rare disease:

1- Companies that want large markets and use old technologies: These are your classical large pharma companies, that have the pockets that are needed to pay for clinical development in large diseases, and that are developing a traditional drug, usually a small molecule that can improve an important symptom. These companies have transformed the way we treat common diseases like diabetes or cardiovascular diseases and still produce the same type of drug, but today the problem is the market push that scares them away for the large diseases because there is too much competition and the requirements for pricing and reimbursement are too high. This is how a company that had a drug perfectly good for a large market, and that prefers large markets, finds itself developing their molecule for a rare disease that has that common symptom in order to avoid the competition.

2- Companies that want small markets and use old technologies: Some companies develop the same type of molecule that could treat common diseases but have decided to focus on rare diseases as part of their business model. This is usually the case of smaller companies, which don’t have sufficient money to go after the common diseases. Smaller companies often focus on smaller diseases because those are the ones where they can afford to take a drug all the way through clinical trials and into the market. A second type is when the molecule is an old drug. In these cases the orphan drug market exclusivity that I described before becomes very important and makes the company focus on a rare disease so that they can have product protection (since they don’t have a patent on the drug because it is an old drug). These companies focus on rare diseases because it is cheaper to take orphan drugs to the market and because of the market exclusivity.

3- Companies that want large markets and use new technologies: Some of the large companies, which like to go after large diseases, are also adopting new technologies. This allows them to go straight to the cause of the disease, in what we could consider personalized medicine. In these cases where the therapy targets a disease cause, not just a symptom, rare diseases that share that cause become very attractive as part of the drug development pathway. Imagine for example a company that wants to develop a medicine for Alzheimer's disease by creating a molecule that targets the protein “tau”, which is very important in Alzheimer's. Such company knows that most trials in Alzheimer´s disease fail, and that they cost many hundreds of millions of dollars. So such company will most likely choose to first test their drug in some monogenic taupathy (i.e. a rare disease caused by a problem in tau) to make sure that the drug does what it should, before risking costly Alzheimer’s disease trials. The rare disease becomes a stepping stone in the development program. This is another scenario in which a company that is going after a large market finds itself developing their molecule for a rare disease in order to de-risk their program.

4- Companies that want small markets and use new technologies: And last we have the companies that are focused around a technology platform that usually means they can target genetic causes. These companies working on new technologies such as gene therapy and other personalized-medicine approaches work on rare diseases because these are largely caused by genetic problems, so they are the perfect match for companies (large and small) that are using the new technologies. These are the companies most likely to specifically develop from scratch a therapy ideally designed for that rare disease, and to target the cause. These are the companies (and the business scenario) most likely to lead to the type of treatments that we could call cures.

Some diseases become popular for only of these business reasons. Others fit multiple boxes. It is important for each rare disease patient organization to identify which of these boxes they fit, so that they know how to target their efforts and conversations.

PART 2 – CHOOSING ONE SPECIFIC DISEASE

Q1 - Does it fit our business needs?

Your rare disease will be attractive for a drug development company if it matches one of the four main business propositions (previous graph):

1 - My drug discovery expertise is in epilepsy. The field of epilepsy got very crowded, with over 30 drugs approved, so pretty much every company in the sector started looking at the orphan epilepsies to avoid the competition. Except for some cases, most of their drugs are molecules that could have easily treated epilepsy in general, since they just treat the symptom (seizures) and not one of the many epilepsy causes. But the companies chose to work on the orphan space to avoid competition. That is how rare syndromes with epilepsy “got lucky”. Prader-Willi might be an attractive target for a company that is concerned about competition in the obesity market. Neurodegeneration is another field where companies are moving towards rare diseases, in this case due to the high failure rate in the larger diseases. If your disease has a common symptom and the general market is saturated it might attract these companies.

2 - A company with an old molecule will most likely be looking for a rare disease due to the need of securing some years of market exclusivity in the absence of a drug patent. Often this happens when the company has discovered a new property that the old drug has, which creates the possibility of developing for that new use. In this case they will be looking for a rare disease that matches that new use, either due to its cause or due to its symptoms. Also, some small companies developing molecules that could treat broad diseases choose to focus on the orphan space because they can't afford the large and lengthy trials that broader diseases demand. One example could be the multiple small companies going after autism, which often decide to target genetic syndromes with autism even if their drug is not specific for the syndrome.

3 - The large company that is targeting a molecular cause of a large disease will most likely be interested in identifying a rare disease that results from that same cause. Some diseases become quite popular as monogenic examples of large diseases. I am a neuroscientist, so I often use taupathies as an example of stepping stone. Gaucher disease also shares biology with some forms of Parkinson, so companies targeting glucocerebrosidase for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease are likely to run their trials first in Gaucher’s disease and only risk moving forward with Parkinson if the drug has good results. There are examples of this strategy in all disease areas.

4 - Companies or research programs that are built around a platform technology often have a series of requirements that the target disease must meet in order to be a good match for the technology. A good example is a great young company called Stoke Therapeutics, which has discovered a way to increase protein levels by targeting a step between the gene sequence and the protein production (excuse my vague descriptions for the sake of non-expert understanding). Because of their particular technology, Stoke is interested in diseases that couldn’t be treated with gene therapy (maybe because the gene is too large for “traditional” gene therapy), that is also not amenable to protein replacement approaches (so the protein cannot be a soluble enzyme, for example), that needs more levels of a given protein (and not less levels) and that has one good copy of the gene for their therapy to act on. Each technology will impose a different set of requirements.

It is important to remember that the same disease might be a good match for one of these technologies AND be mechanistically linked with a broader disease so it can be a stepping stone AND have some common symptom that makes it attractive for the opportunistic companies. In other words, each company might be interested in your rare disease for a whole different reason!

Q2 - Is the field already mature?

The previous question asked whether a particular company should be interested in your disease. The question about field maturity essentially asks if they should be interested in your disease NOW. It will also help prioritize which disease to focus on where multiple rare diseases match the needs of the company or the drug that they are already developing.

We will discuss this in the next entry of the Impatient Series.

In the meantime, let’s start an #ImpatientRevolution!

Ana Mingorance, PhD